After forks, pins are the next most basic chess tactic. In a pin, a Bishop, Rook, or Queen immobilizes an enemy piece – if that piece moves, a more valuable piece behind it will be attacked and taken. Only a Bishop, Rook, or Queen can pin because they are long range pieces and can “x-ray” through a piece.

Note! The pin is often confused with the skewer. In a pin, the piece in front cannot or should not move. In a skewer, the piece in front must move.

The distinction between a relative pin and absolute pin is not terribly important but it’s also not too difficult to understand.

In an absolute pin, the pinned piece cannot legally move whatsoever. Absolute pins only happen with pieces pinned to the King, because moving that piece would put yourself in check which is illegal.

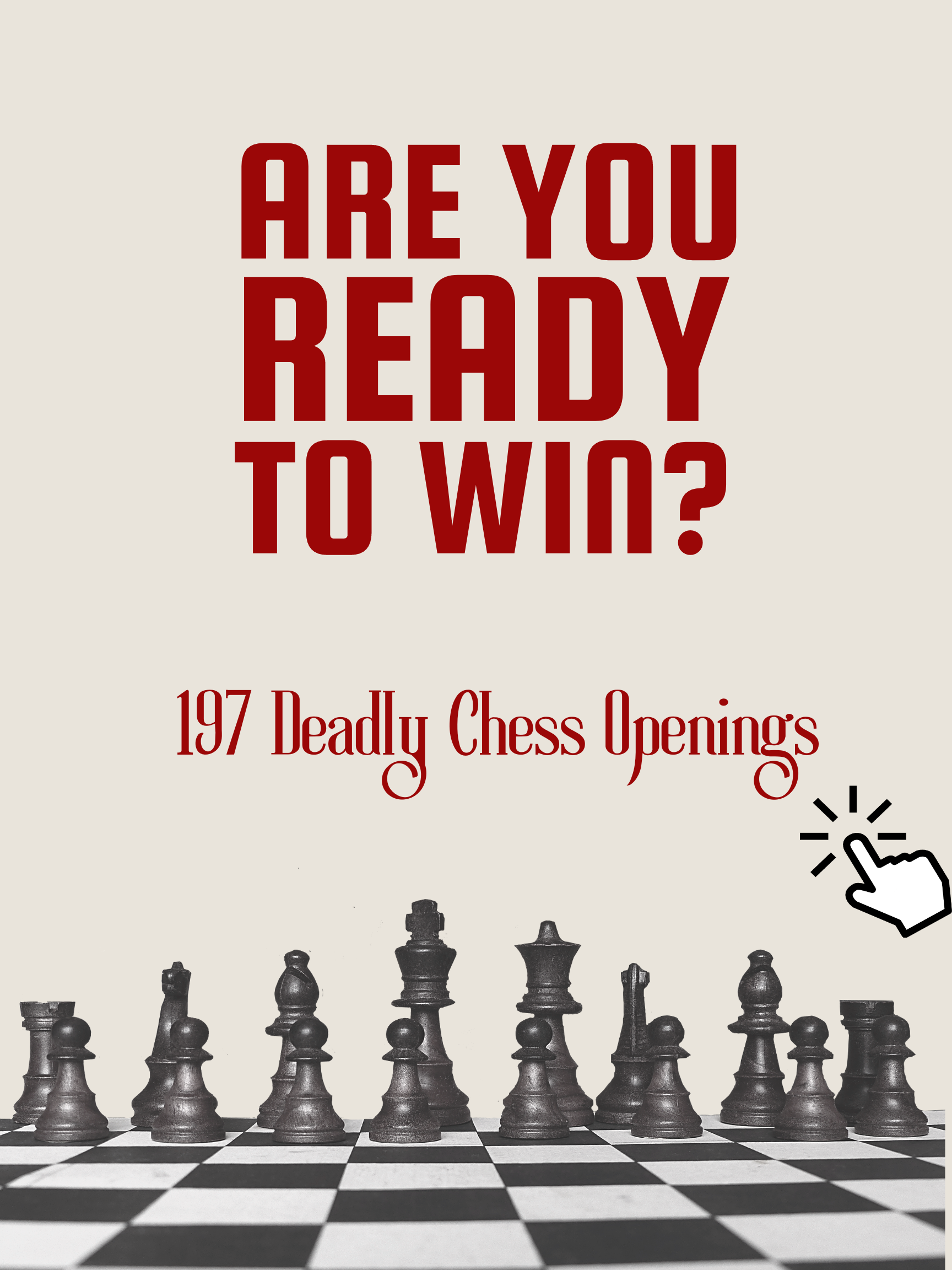

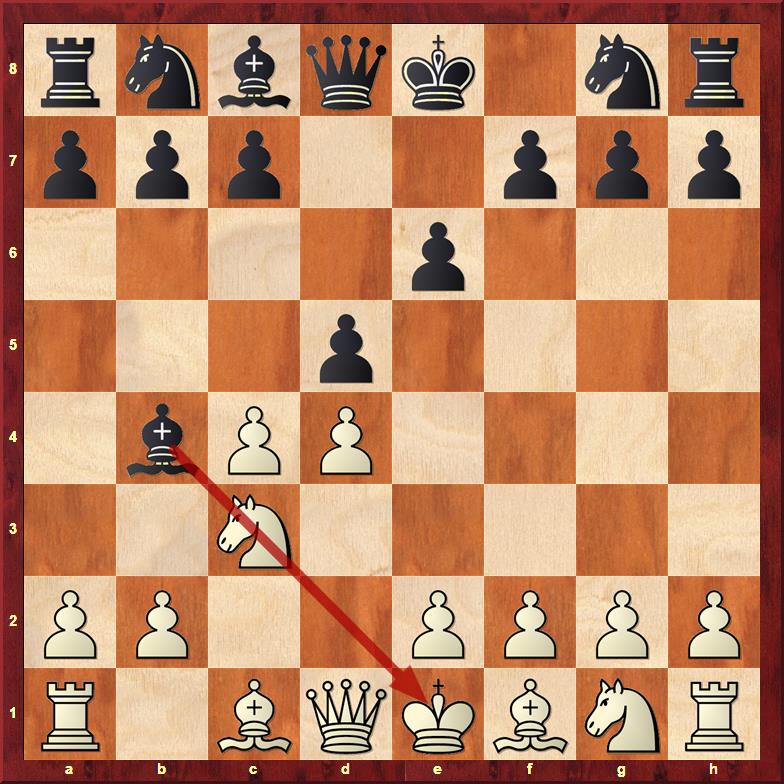

The first image in the gallery above gives us an example of an absolute pin in the Queen’s Gambit Declined. If the Knight moves, the White King would be in check

In contrast to an absolute pin, a relative pin is where you can move the pinned piece but don’t want to because you would lose a more valuable piece behind it.

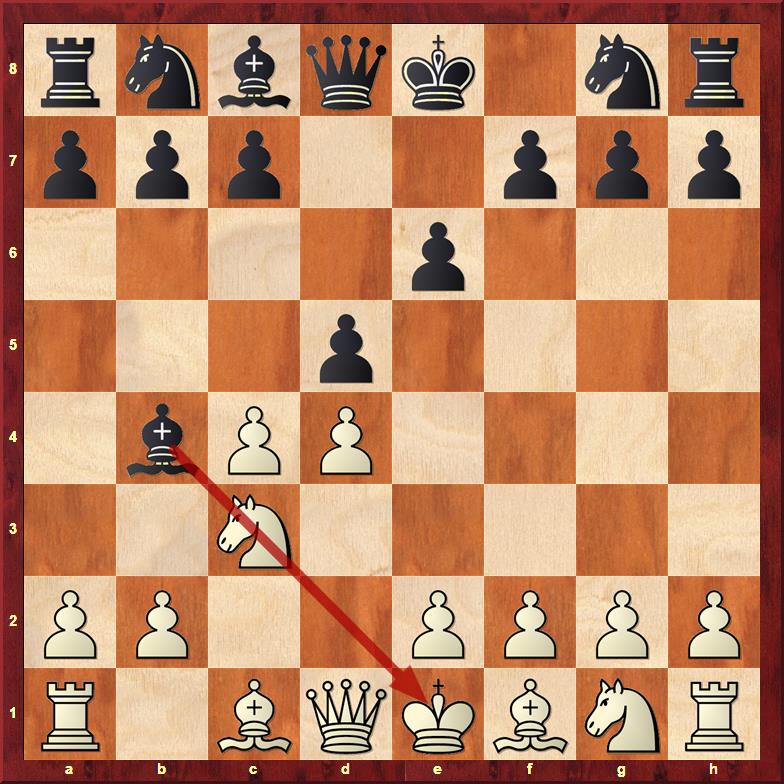

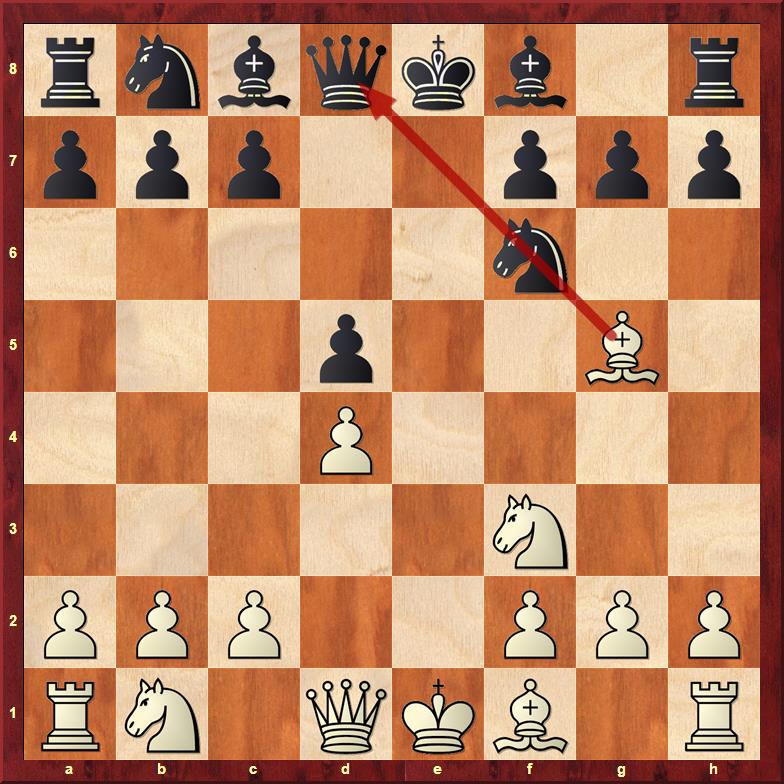

The 2nd image in the gallery gives us an example of a relative pin in the French. The Black Queen would be captured if the Knight moves. Since the Black Queen is more valuable than the White Bishop, this would be a bad trade.

The most important takeaway from this article is to … PILE ON PINNED PIECES!!

The pinned piece cannot move. If you keep bringing more and more pieces to attack it, eventually you’ll overcome the opponent’s defenses and win it*!

*Usually, of course. As Ben Franklin said, “Nothing in life is certain except death and taxes.”

You’ve been pinned! What do you do? Simply break it!

To break a pin, either:

Coming soon: Check out the series “Destroying the Pin in Style”!

Let’s look at an example of each way to break a pin.

The reason a pinned piece can’t move is because a more valuable piece behind it would get captured. Thus, one way to break the pin is to simply put a less valuable piece behind the pinned piece instead.

A very common example of this is when Black develops his Bishop to e7/d7 to stop a pin by White’s g5/b5 Bishop (respectively).

Another way to deal with the pin is simply to move the valuable piece away so there’s no more pin. Makes sure to read the **disclaimer** below though!

**Beware**

Make sure the pinned piece is adequately protected otherwise it can be taken.

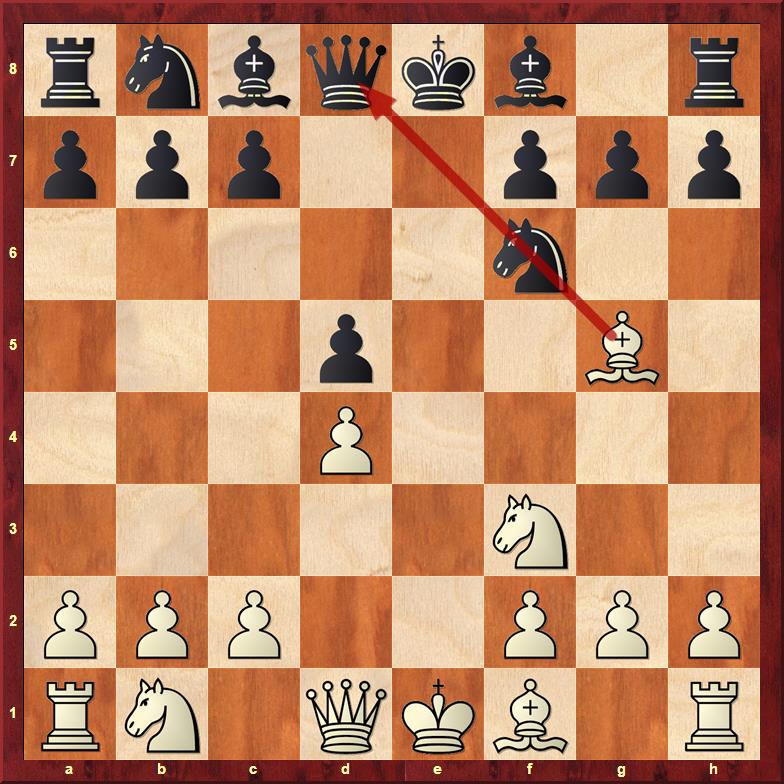

Usually adequate protection = 1 more defender than attacker. The next position is an example of this mantra. Although the Knight is protected once by a pawn, the Bishop could take the Knight if the queen moves and leave you with doubled pawns. [Pros & cons of doubled pawns]

The third point is probably the most intuitive. One very common example is in the Ruy Lopez when Black “puts the question” to White’s feisty bishop. Does the bishop want to take the Knight or retreat?

Poll: What further questions do you still have about pins? Drop your answer in the chat.

All credit goes to Chess.com & Simon Williams